2010 from the International Directory of Company Histories

Statistics:

Private Company

Incorporated: 1946 as Leblanc USA

Employees: 500

Sales: $65 million (2001 est.)

NAIC: 339992 Musical Instrument Manufacturing

Company Perspectives:

No other manufacturer can offer as wide a selection of brass and woodwind

instruments crafted with the same integrity and dedication to excellence as does

Leblanc. Through all stages of the company’s growth, advancement and

acquisitions, it has never lost sight of the principles on which it was founded.

Long ago, Georges Leblanc established the basic tenets of integrity,

musicianship and creativity for his firms to live by. At G. Leblanc Corporation,

these principles still live on, propelling the company into the 21st century.

Key Dates:

1750: Noblet is established in France.

1904: Noblet passes the business to the Leblanc family.

1921: Leblanc begins distribution of clarinets in the United States.

1946: Pascucci founds Leblanc USA in Kenosha.

1964: The company acquires the Frank Holton Company.

1971: The company acquires the Martin Band Instrument Company.

1989: A 65 percent interest in the French parent is acquired.

1993: A U.S. firm completes the acquisition of Leblanc S.A.

2000: Leon Leblanc dies; the U.S. plants are expanded and upgraded.

Company History:

The G. Leblanc Corporation is one of the world’s leading makers of woodwind and

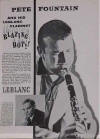

brass instruments. The company manufactures instruments under the brand names

Leblanc, Noblet, Normandy, Vito, Holton, Martin, and Courtois. Leblanc’s Holton

subsidiary is the world’s largest maker of French horns, and makes other brass

instruments as well. Leblanc’s Martin subsidiary is known for an esteemed line

of trumpets, and specializes in smaller brasses. Leblanc also manufactures

instrument cases and woodwind mouthpieces. Leblanc operates three factories in

the United States, in Kenosha and Elkhorn, Wisconsin, and one plant in La

Couture-Boussey, France. The company was originally set up as a joint venture

with a French company, Leblanc S.A. Leblanc S.A. was one of the oldest

corporations in France, tracing its roots back to 1750. Leblanc USA purchased a

majority interest in the French company in 1989, then acquired the entire firm

in 1993. Leblanc has been a key promoter of school music programs in the United

States from the 1950s onward. The company manufactured an improved line of

instruments for beginning students and helped establish the type of instrument

rental practice that is now an industry standard. The company helped organize

the school musical instrument sales industry, and its efforts led to the

founding of the National Association of School Music Dealers.

18th-Century French Antecedents

The G. Leblanc Corporation harks back to the reign of Louis XV in France. The

king promoted music at his court, leading to a new French musical instrument

industry. The firm of Ets. D. Noblet was founded in 1750 in La Couture-Boussey

to make woodwind instruments. Noblet was known for its clarinets and helped make

France a European center for woodwind manufacturing. Members of the Noblet

family operated the company until 1904. In that year, the last Noblet died

without an heir, so the firm passed to Georges Leblanc. Leblanc was also a

member of an illustrious family of woodwind makers, thought to be the best at

his craft in all France. His firm, G. Leblanc Cie., was centered in Paris.

Leblanc continued to manufacture the Noblet line of clarinets at La Couture-Boussey,

while making improvements to Leblanc instruments in his Paris workshop. The

business was a family affair. While Georges fought in World War I, his wife

Clemence managed the factory. Later his son Leon greatly expanded and improved

the business. The Leblanc family also worked with Charles Houvenaghel, a famed

acoustic scientist. Houvenaghel and Leblanc set up an acoustical research

laboratory, the first of its kind, and applied their research to instrument

manufacture. Leblanc and Houvenaghel designed new clarinets in unusual ranges.

They eventually made a line of clarinets ranging from the piccolo-like sopranino

to the extremely low octo-contrabass–a whole clarinet choir, with a greater

pitch spread than a string orchestra.

Leon Leblanc took his company’s scientific principles even farther. Leon was

a gifted clarinetist who took the top prize at the Paris Conservetoire as a

young man. Although he could have had a great career as a performer, Leon chose

to stay with the family business and apply his musical insight to instrument

manufacture. He dedicated his life to bringing acoustical, mechanical, and

musical improvements to woodwind instruments. Although Leblanc’s instruments

were almost entirely handmade, Leon Leblanc insisted that the craftsmen follow

careful measurements. “Music is an art, but it is still governed by the laws of

science,” he declared (Music Trades, July 1996). As a result, Leblanc

instruments were more consistent than those that had come before. The company

continued to strive for consistent quality, ease of playability, and mechanical

innovation, throughout its history.

Postwar Beginnings of the American Firm

G. Leblanc Cie. had worked with an American distributor since 1921. It gave

exclusive rights to U.S. distribution to Walter Gretsch, who ran the large

musical instrument company Gretsch & Brenner. Although the Leblanc family had

strong personal ties to Walter Gretsch, the arrangement had many problems. The

Leblanc instruments came from France by sea, and arrived in New York in terrible

shape, out of tune and sticky from two weeks of exposure to damp and cold.

Gretsch sold the instruments in this condition, much to the distress of the

French manufacturer. But because Gretsch handled many product lines, he did not

devote particular care to the Leblanc clarinets, and he did not have the time to

acclimate and recondition the imports. Thus, the Leblancs were already thinking

of an alternative to this distributorship when they met a young U.S. soldier in

1945. This was Vito Pascucci.

Pascucci grew up in Kenosha, Wisconsin, the son of Italian immigrants of

modest means. His family had a musical bent, and Vito began playing the trumpet

as a young boy. By the time he was 12, he was traveling to Chicago on weekends

for lessons. After his lesson, he used to stop in at the Chicago Musical

Instrument Company and watch the repairmen. When he was a teenager, he began

repairing instruments in the back of a music store run by his older brother,

Ben. In 1943, Pascucci was drafted into the army. He applied to join the army

band, and was given a spot as the band repairman. Pascucci’s band included three

former members of the Cleveland Symphony, and with this kind of competition, he

could not make it as a trumpet player. But later the famed swing band leader

Glenn Miller began putting together his own army band. He snagged the symphony

players, and they recommended he take Vito Pascucci as well. When Pascucci got a

letter ordering him to report to the Glenn Miller band, he thought it was a

hoax. Pascucci spent days trying to get the letter authenticated. He had no idea

how Miller would have heard of him. When they finally met, Pascucci recalled

that Miller treated him like a nonentity. But Pascucci had a chance to show his

skills when a bandmate came to him with a smashed trumpet that he needed to be

able to play the next morning. Pascucci worked all night and repaired the

damaged trumpet with only a broomstick. Miller was impressed, and they began

having lunch together every day. They became good friends, and came up with a

plan to launch a chain of Glenn Miller Music Stores when the war was over. They

planned to import European instruments, which were of better quality than

U.S.-made ones.

Glenn Miller’s plane disappeared over the English Channel on December 15,

1944. Pascucci was crushed at the loss of his friend. Nevertheless, he went on

with plans he and Miller had made, and arranged to visit musical instrument

factories in France. He wanted to meet the maker of Noblet clarinets, because he

had seen those instruments at the Chicago Musical Instruments store he used to

haunt as a child. Someone directed him to the Leblanc factory in La Couture-Boussey,

where he met Georges and Leon Leblanc. The family had suffered during the German

occupation. The Leblancs had had to trade clarinets for food in order to

survive. The factory was down to only 20 workers, and raw materials were

virtually non-existent. But the family instantly took to the young American

repairman, showing him the workshop and teaching him some new skills. When he

told the Leblancs about the Glenn Miller Music Stores idea, they instead asked

him to distribute their instruments in the United States. Pascucci was taken

aback. He felt that he did not know enough about business to take on such a

responsibility. But the Leblancs liked him and trusted him. He left the factory

with a duffel bag full of clarinets, and Leon Leblanc promised to meet him in

the United States when the war was over.

Leblanc kept his promise and wired Pascucci to come to New York in 1946. The

first order of business was to sever the firm’s relationship with Gretsch &

Brenner. Walter Gretsch had died, and the Leblanc business contract had passed

to his daughter Gertrude. Gertrude happened to be married to John Jacob Astor,

one of the wealthiest men in the country. Pascucci could not believe Leblanc

would choose him, a poor Wisconsin boy, to run the U.S. distributorship, rather

than the Astors. But all this worked out, and Pascucci entered a 50-50

partnership with G. Leblanc Cie., forming Leblanc USA in May 1946. Although

Leblanc had wanted Pascucci to work in New York, where the musical instruments

import business was centered, Pascucci insisted on returning to his hometown. So

he signed a lease for a tiny storefront in Kenosha. He began by taking in the

Leblanc instruments and making them playable, something Walter Gretsch had never

bothered to do. Demand for musical instruments was on the rise, with the war

over and a return to peacetime activities. With the baby boom that followed the

war, school music programs also grew quickly, and Leblanc USA began supplying

inexpensive instruments for beginners.

Expansion in the 1960s

The school market was the best opportunity for the young company, as the

country’s school-age population swelled. The company began importing

inexpensive, durable instruments that were easy to play. It began in the 1950s

with a line of metal clarinets. But plastic clarinets were already popular, so

the firm abandoned metal and began making plastic student instruments. Demand

was so great that the French factory could not supply enough. So Leblanc USA

began manufacturing its own instruments for the first time, forming the plastic

bodies and fitting them with French-made keys. This new line was given the name

“Vito.” Eventually the entire “Vito” clarinet line was made in Kenosha,

including the keys. The small factory expanded in 1953, and then again several

times in the 1960s.

Leblanc worked to tame the school music industry, which had been a highly

fractured market. In 1950 the company hired a music educator, Ernest Moore, to

work on educational programs and materials for music teachers. Leblanc was the

first wind instrument manufacturer to hire a music educator, and it continued to

keep the post filled with distinguished pedagogues up to the present time.

Leblanc also began organizing monthly meetings for musical instrument dealers,

giving them a chance to compare notes and discuss ways to improve the business.

The dealers who met under Leblanc’s auspices adopted a rent-to-own policy,

whereby students rented an instrument for a year and the payments could be put

toward an eventual purchase. This became the standard way the student music

industry worked, and it made sense for both the students and the instrument

dealers. Some of the dealers who had met at the Leblanc meetings later organized

the professional group the National Association of School Music Dealers.

By the late 1950s, Leblanc had become a major player in the school music

industry. But its product line was limited to woodwinds. In 1964 the company

acquired the Frank Holton Company, a maker of brass instruments. Holton was

founded in Chicago in 1898 by a former trombonist with the John Philip Sousa

band. In 1917 Holton moved to Elkhorn, Wisconsin. Leblanc bought the company,

gaining its dominant Collegiate brand of student brass instruments. Under

Leblanc’s management, the Holton company began improving its French horn

manufacturing. The firm developed a prized line of French horns, valued by

professional players around the world. Holton eventually became the world’s

largest manufacturer of French horns. It also makes trombones, euphoniums, and

other large horns.

Leblanc diversified further in 1968, when it bought The Woodwind Company.

This was a small company that specialized in making woodwind mouthpieces. Around

the same time it also bought an instrument case manufacturer, the Bublitz Case

Company. Bublitz was based in Elkhart, Indiana. In 1971 Leblanc bought another

Elkhart company, the Martin Band Instrument Company. Martin was the oldest band

instrument manufacturer in the country, excepting the time it had been closed

down for the Great Chicago Fire. It made a line of brass instruments, including

the Martin Committee trumpet, an instrument still prized by jazz players today.

Leblanc closed down Martin’s Elkhart plant and moved manufacturing to a new

facility in Kenosha. Leblanc also cut the overlap between its two brass

subsidiaries by concentrating the making of trumpets and other small horns at

Martin and letting Holton specialize in the larger instruments.

Leblanc expanded its facilities to make room for the new product lines and

updated the Elkhorn and Kenosha factories. Leblanc constantly improved the

technology it used to build instruments, following Leon Leblanc’s dictum that

science governed music. The firm designed and built much of the machinery it

needed to automate the manufacturing process. Pascucci also insisted that the

factory be a pleasant place to work, despite the prevalence of machines. Workers

looked through glass walls into a garden, and quiet hallways were hung with

paintings. Pascucci himself continued to innovate, developing new manufacturing

methods as well as new models and new instruments. The company prepared for five

years before it began making a new instrument, the descant horn, in the 1970s.

By 1980, Leblanc had become the third largest manufacturer of wind instruments

in the United States.

Buying the French Firm in the 1980s

In 1975 Pascucci’s son Leon (named for Leon Leblanc) joined the company,

beginning as vice-president for advertising. The younger Pascucci contributed to

the striking interior design of the Leblanc headquarters, and became known for

staging beautiful exhibits at industry trade shows. He seemed to have the

artistry and flair that was vital to the firm’s image. In the 1980s, Vito

Pascucci began thinking of buying out the French firm. Leon Leblanc, born in

1900, was an elderly man with no heirs. It seemed natural that Pascucci would

take over. He and his son would continue to run the company along the lines

Leblanc had established. Pascucci began seriously negotiating the sale in 1986.

Leblanc himself was all for giving Pascucci control. But the transaction

involved selling one of the oldest businesses in France to an American, and this

was difficult for the French government to abide. When Pascucci made his first

inquiries, the French Ministry of Trade told him that odds were 100 to one

against his ever buying Leblanc.

Over the next three years Pascucci made more than 20 trips to Paris to meet

with French government officials. Because of the age of its Noblet subsidiary,

Leblanc was considered a national treasure. Pascucci finally won approval to buy

65 percent of Leblanc S.A., as the French company was then known. But the deal

was so sensitive that the French prime minister, Francois Mitterand, had to okay

it. After the purchase, the Leblanc company sent a survey to clarinetists all

over the world, asking their input for future clarinet models. The company then

brought out a new line of improved instruments, which were made at the French

factory in La Couture-Boussey. In 1991, Leon Pascucci became president of G.

Leblanc Corporation. In 1993, the U.S. firm completed its acquisition of Leblanc

S.A., acquiring the remaining 35 percent of the company. The new legal

arrangements made little difference to how the company operated. The French

factory employed about 100 workers, and the U.S. factories about 400. Overall

sales were estimated at $37.5 million.

New Technology in the 2000s

Leon Pascucci was credited with continuing the drive toward automation at the

company. This meant not only in the factory areas but in accounting and sales.

Pascucci also served as president of the National Association of Band Instrument

Manufacturers, an industry group that helped raise money for school music

programs. He also helped the city of Kenosha raise funds for a bandshell on the

Lake Michigan shore, and sustained the community band and orchestra. In 2000,

the company began a multimillion dollar expansion. The main Kenosha plant

doubled in size, and the company brought in scores of new machines. The firm

stopped using toxic materials, such as brass cleaners, in favor of

environmentally sound and efficient processes like sonic buffers. Leon Leblanc

died that year, at the age of 99. The company was still operating on the

principles he had laid out, with mechanical efficiency wedded to artistic

production. In 2001 the G. Leblanc Corporation was given an “Industry World

Leadership” award by the Wisconsin Manufacturers & Commerce association, the

state’s largest business group. The award noted the bold steps the company had

taken in implementing new technology.

In 2003 the company’s French factory was damaged by a suspicious fire. The

ancient La Couture-Boussey plant suffered more than $3 million of damage, but

volunteer fire fighters put out the flames before the building was destroyed.

Although some inventory was lost, the factory’s valuable stock of antique

hardwood was not harmed. The factory was back in production about two months

after the fire.

Principal Subsidiaries: Frank Holton Company; Martin Band Instrument Company;

Woodwind Company; Bublitz Case Company.

Principal Competitors: Conn-Selmer, Inc.; Yamaha Corporation.

——————————————————————————–

Further Reading:

■ Bednarek, David I., “G. Leblanc Strives for Perfect Pitch,” Milwaukee

Journal, June 20, 1993, p. B1.

■ Dunn, Michael J., III, “The Musical World of G. Leblanc,” Wisconsin Trails,

Summer 1980, p. 35.

■ “Improving Productivity and Quality, Pursuing the Perfect Clarinet,” Music

Trades, July 2000, p. 162.

■ “Leblanc Turns 50,” Music Trades, July 1996, p. 134.

■ “Leblanc U.S. Buys Leblanc Paris,” Music Trades, June 1989, p. 34.

■ “Leon Pascucci Named Leblanc CEO,” Music Trades, December 2001, p. 145.

■”U.S./French Collaboration at Leblanc Yields New Pro Clarinets,” Music Trades,

January 1991, p. 53.

Source: International Directory of Company Histories, Vol. 55. St. James

Press, 2003.